(an excerpt from a forthcoming memoir by Nowick Gray, My Generation)

In the winter term (1971) I explored an intriguing new avenue of expression, one also well suited to the temper of the time. Musical Sound Awareness was taught by a black jazz musician, Robert Northern, who on the first day said to the class, “Call me Ah.” He wore a blousy yet masculine, black-and-orange checked dashiki and pointed black shoes, and dark purple fez. His manner was casual, yet charged with inspiration; he possessed and modeled an easy grace of motion and speech.

Sixty non-musicians like me sat in bleacher-style seats and clapped, grunted, tapped, whistled, banged, drummed, hooted and beat on whatever instrument came to hand—conga or harmonica, African thumb piano, shaker, bell or sticks. The key was rhythm—making up one part and matching them together, sixty sound tracks melded into one cohesive whole.

For inspiration and understanding of the underlying concept of musical appreciation, Ah gave us a simple homework assignment the first week: to listen to the sounds of nature. I heard the calls of crows, and the tock-tocking of woodpeckers, merging with the adagio of trees in the wind, in mystical orchestration.

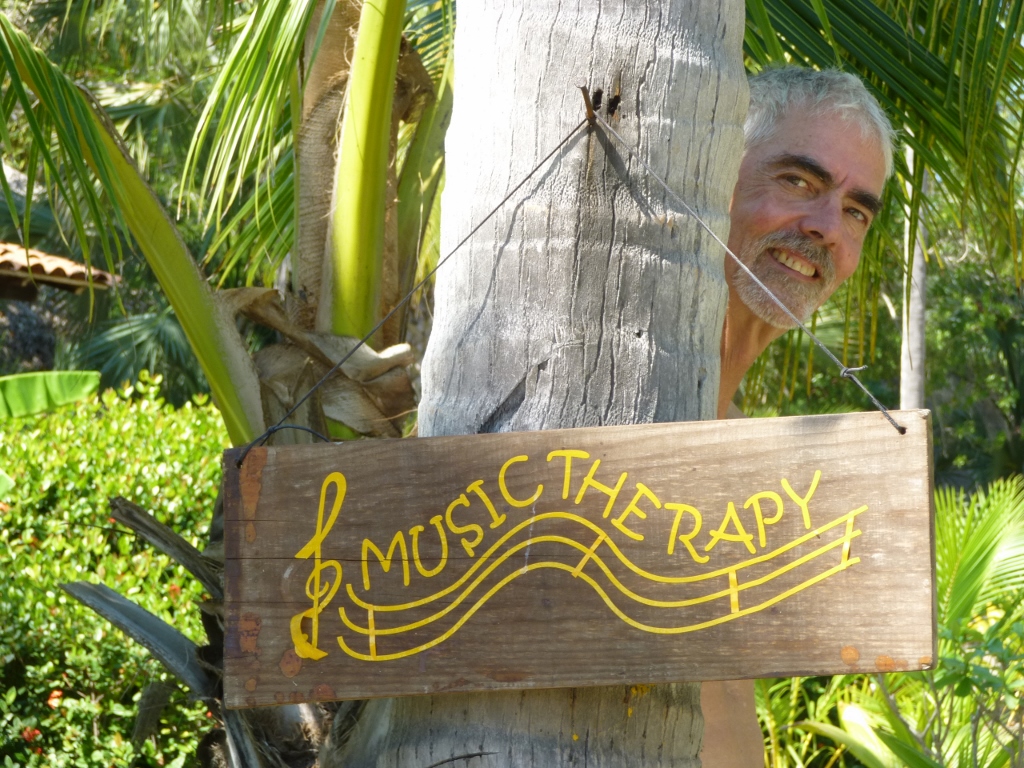

And what about the swishing of traffic, the distant voices of students calling across the Green? I decided they could all be part of the mix, too. Twenty years later I would take up African drumming, and host a 24-hour jam where the only rule was “Keep the beat.” Exiting the Argenta community hall in the morning, I recalled this earlier moment of musical sound awareness, as the crows carried on the beat when the drums fell silent.

Back in class, I tried my hand at the conga drums, wanting to channel Santana, or perhaps my future drumming self. But it was a lame first attempt, and the spot audition certified a couple of black guys with more experience and talent. I settled for the miscellaneous percussion.

“Just jam with it,” Ah said. “You got to hear where to fit your sound in. The parts all fit to the central pulse, see, which is the silence, the breath, the heartbeat, the wind. You hear me? Yeah. Okay, hit it.”

Chang, chang, chang, chock-chock…

It actually worked; we made music.

Ah’s friend Dizzy Gillespie flew up one day to wow us with his wit and wild trumpet. I had never followed the jazz scene much, despite my boyhood fascination for trumpet legend Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong. But that once-nursed glimmer of a dream to play jazz trumpet now stood embodied in the brown man with his signature ballooning cheeks blowing notes like the very voice of freedom itself.

I found it at once exciting and humbling to recognize how wide the gap was from childish dreams to celebrity performer. Yet that gap dwindled in this intimate human connection, in the informal class setting.

Ah announced that for the course finale, the class would perform in the college auditorium for a public audience. I proposed to recite an original poem, “Starshine,” to be accompanied by sequential improvisations of various instruments. Each stanza celebrated one of the planets with its own characteristic mythical imagery and orchestral coloring.

“Hey, that’s far out,” Ah said to me. “You know what you do for this? You go to the theatre department, they got a wardrobe room upstairs, and you ask them for a magician’s robe—and one of those tall, pointed hats, with stars on it. Oh yeah,” he said, clapping his hands together, smiling, and rolling his eyes momentarily to the ceiling, “I can see it now.”

I did as he instructed and, come performance day, found myself floating around on stage in my black, star-studded robes, gesticulating to the heavens and exhorting my haywire orchestra to accompany the otherwise forgettable verses I intoned into the microphone.

Ah sprung a last-minute surprise by bringing up some real jazz musicians from New York City to back us up. Their delicate tinklings and swirling whistles elevated the performance of “Starshine” from noise to art, helping all of us to earn a gratifying round of applause.

I discovered in Ah’s course that anyone can play, even perform. The supposed boundaries between art and nature, music and sound, even professional and amateur, had been blurred, even erased. And the difference in self-concept between inept and accomplished could be bridged simply by donning the proper costume and attitude, and by getting up there and doing it.

I didn’t yet know my inspiration was sparked then to learn the craft of music, decades down the road. I wanted most of all to be able to jam, playing hand drums. But to do it well would require learning the rudiments and practicing technique. Opportunity and dedication aside, there was no denying the special talent some possessed to produce music of surpassing genius; and in that respect, no one could touch Hendrix. I sang his praises in every discussion comparing rock stars, and always played his records when I felt the highest, or lowest.

I didn’t yet know my inspiration was sparked then to learn the craft of music, decades down the road. I wanted most of all to be able to jam, playing hand drums. But to do it well would require learning the rudiments and practicing technique. Opportunity and dedication aside, there was no denying the special talent some possessed to produce music of surpassing genius; and in that respect, no one could touch Hendrix. I sang his praises in every discussion comparing rock stars, and always played his records when I felt the highest, or lowest.

Further reading: 50 years after: Woodstock on the Beach

Free ebook: Friday Night Jam

Free ebook: Friday Night Jam

Order now:

Kindle eBook – Now FREE at: Amazon.com | Amazon.ca

Paperback: Amazon.com | Amazon.ca

Free ebook:

Free ebook: